- Home

- Spencer Gordon

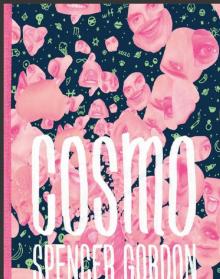

Cosmo

Cosmo Read online

Coach House Books, Toronto

copyright © Spencer Gordon, 2012

first edition

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. Coach House Books also acknowledges the support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit.

While some of the characters in these stories take their names from real-life personages, their personalities and behaviour should be read as entirely fictional — they bear no resemblance to the persons whose names they share. Everything in this collection is a product of the imagination of the author.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Gordon, Spencer

Cosmo / Spencer Gordon.

Short Stories

eISBN 978-1-77056-331-5

I. Title.

PS8613.O735C67 2012——C813’.6——C2012-905208-6

Cosmo is available as a print book: ISBN 978-1-55245-267-7.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyright material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author's rights.

Table of Contents

Operation Smile

Jobbers

Journey to the Centre of Something

This Is Not An Ending

Frankie+Hilary+Romeo+Abigail+Helen: An Intermission

Wide and Blue and Empty

The Land of Plenty

Last Words

Transcript: Appeal of the Sentence

Lonely Planet

OPERATION SMILE

This is authentic, Crystle thought. The turquoise scrubs, the sky-blue smock. The military watch and the brush cut. The man spoke slowly, deliberately, gestured emphatically with his hands. She noted the fine polish of his fingernails, his trimmed cuticles, the skin softened by constant scrubbing. This is a man who cares about his appearance, she thought. That’s refreshing; I could talk to this man.

It was significant that Commander Kubis didn’t seem nervous. Most men were nervous or jittery around her. It didn’t matter that they fought wars or made policy or saved lives, worked with living tissue, bore immense responsibilities. When confronted by all that beauty and poise, most were reduced to stammering, wide-eyed children. The only men who weren’t usually nervous were the actors and millionaires, because for them, she assumed, beauty was simply functional, like furniture.

‘Take a look around you,’ Kubis said, smiling. ‘And don’t be afraid to get a bit close and cozy. Even on a day like today, there’s lots of work to do.’

Commander Kubis (Kenneth, she remembered) was director of Surgical Services. It was a title that carried a certain weight. Maybe I can interview him after the tour, she thought. Document his struggles, his motivations, record his climb to seniority. She had to profile common, everyday sort of people as well as the celebrities, the big names. It was good to think about the book, the future, now, because she would have trouble remembering it all later. These stories, this journey: it was what would distinguish her manuscript from others, what would elevate her work in the eyes of publishers. She understood that distinguishing herself was vital, that such a chance would not come again.

Crystle Danae Stewart, Miss U.S.A. 2008, stood six feet from Commander Kubis aboard the USNS Mercy. She was on the far right of a small semi-circle of women, flanked on her left by Jennifer Barrientos, Miss Philippines; Samantha Tajik, Miss Canada; Simran Kaur Mundi, Miss India; and Siera Robertson, Miss Guam. Crystle knew only their first names. In her opinion, they were five of the most attractive girls in the competition. They were all brunettes, and tall, their average skin tone being a dark caramel. It was refreshing to be away from America’s monopoly of blond hair and blue eyes, the expectation to be vivacious yet neighbourly, if a touch naive.

If they could only just shut up, Crystle thought, these girls could be the A-Team. Aside from Miss Canada, the other three suffered from typical sorts of ESL problems: twisted vowels, torturous locution. Jennifer’s accent was so horrendous that it was almost funny, and Guam (though wisely quiet) was so obviously taking a day off in terms of cosmetics and wardrobe that Crystle was embarrassed for her. She resented Guam for wearing the ridiculous Mercy baseball hat, the worn-in jeans. It was an all-too-easy trick, and one Crystle knew well: trying to look like you aren’t trying, trying to look like the girl next door. Like those bubble-gum girls in her stadium-sized classes at the University of Houston, taking Consumer Science and Merchandising, their hair tucked back through designer baseball caps, wearing snug-fitting sweat pants and immaculate lip gloss. Who were they trying to kid?

Stupid girls, Crystle thought. Stupid Guam. This isn’t a day off.

She was confident that Commander Kubis appreciated her attention, her smart questions and well-timed nods. And, surely, her flattering and respectful attire: a sleeveless black silk blouse, professionally pressed khaki capris. Tasteful gold-hoop earrings, makeup applied with a light touch, hair straightened and tied back. He must be secretly pulling for her, hoping she’d bring the crown home. She was an American, after all, and this was an American military vessel; she felt a small but noteworthy swelling of pride. When he looked in her eyes, she flashed her teeth.

They had been aboard the Mercy, docked in the Nha Trang harbour in southeastern Vietnam, for thirty-five minutes. The five contestants were on a tour of the colossal ship to showcase the altruistic commitments of the Miss Universe competition – a taste of things to come for the winner, who would be obliged to be an ambassador of goodwill and human rights around the world. They had been informed earlier, in a droning summary by a considerably less charismatic shipmate, that the Mercy was acting on behalf of Operation Smile, part of Pacific Partnership 2008: a four-month humanitarian deployment involving a host of nations, staffed by both military personnel and civilian NGOs.

‘We have a total of one thousand beds,’ Kubis said, emphasizing the point with sharp, karate-like chops of his hands. ‘That’s our total patient capacity: a thousand beds. Our wards are ranked by severity of need and degree of care. We go by intensive, recovery, intermediate, light and limited. This room here – this is intensive.’

Crystle watched the other girls gaze blankly over the sky-blue sheets spread taut over the reclining surgical beds. There was a surprising amount of clutter for an or – cords and wiring, wheeled workstations, fire extinguishers and arcane naval gadgets that simultaneously fascinated and frightened her. It was strange, too, that in sections the floor was dark and carpeted – what about spilled fluids? It felt as though she wasn’t on a ship at all, but shuffling along the glossy floors of some giant metropolitan hospital, complete with swinging double doors, lofty ceilings, passing gurneys, even elevators. Descriptions of ge turbines, maximum speeds, information from the National Steel and Shipbuilding Company, basic dimensional summaries – such tedious detail was straining her concentration, making her wary of possible questions or quizzes. All that specialized naval jargon – the raised forecastle, the transom stem, the bulbous bow, the extended deck house with its forward bridge – made her long for a cool shower, the clean white linens of her four-star Diamond Bay Resort hotel room and the guided-meditation tapes she’d forced herself to listen to, if only to calm her nerves. In any case, soon they’d get to the more intimidating stuff: the burn ward, casualty reception,

the morgue (which she hoped they’d pretty much skip).

‘The Mercy is basically a mobile surgical hospital,’ Kubis continued, his smile widening. ‘If we were engaged in battle, we’d be providing medical and surgical support to our Marines and Air Force units. These days, we lend a hand in humanitarian and disaster relief – we’re still busy, even in peacetime.’

It was a hokey, generous smile. Commander Kubis exuded a sort of calm and trustworthy radiance. Obviously a projection of his personality type, she noted. From what she could tell, he was a fine example of her personal philosophy: the alliterative principles of Persistence, Patience and Perseverance. And simply by repeating these three words, Crystle was able to conjure all the familiar comforts of home: sitting in the backyard of her parents’ modest bungalow in Missouri City, listening to the dry winds rattle the high wooden fence and the cicadas sound their motorized whine, a tall glass of iced tea or lemonade sitting nearby on the arm of her deck chair. No thoughts of outfits or makeup or rehearsed responses, simply family time, the heart of ‘Team Crystle’: her homespun support network of friends and co-workers who made the early mornings and the dieting and the exercise less isolating, less liable to break her spirit. Spirit was a concept they’d discussed often, reclining in the backyard on those humid afternoons, her father with his blue Oxford shirt and slippers, her mother clutching at her chest, both of them hanging on her every word, every setback she listed or every doubt she had of her own worth. Spirit was her parents’ hard-working ethos, equal parts secular stick-to-it-iveness and no-nonsense Christianity. Spirit meant character and charity, something to see her through the long haul of the year, the move to New York City and the posh new apartment, the new life of charity balls and careful public appearances. Crystle was reminded daily that spirit meant you were beautiful on the inside – that a person can’t be pretty on the outside and have rotten guts. And even when everything seemed unreal and the world of photographers and journalists and actors swarmed her, she could feel secure if (and only if) she remained a strong, spiritual woman. She had a ‘big responsibility to fulfill,’ her father would add, being such a ‘trailblazer,’ because she was the first 100 percent African-American to hold the title (Chelsi Smith being biracial and Rachel Smith being tri-racial, after all).

Days of discipline, she remembered, of uncertainty and promise. A strong dose of the Bible, Crystle riding in the back seat of their SUV every Sunday and Wednesday to the Emmanuel Pentecostal Church near Murphy Road and Avenue E, standing tall, shoulders thrust back, as the choir unrolled its hymns of judgment and redemption and the oak rafters shook with the sound. Sitting alone on her bed in the quiet hours after the sermon, planners and pens before her, silently reviewing her six steps to achieving goals, the words of advice from her interview and locution coaches who championed the need for preparation and lists – organizational tools that were like bread crumbs lining paths through strange woods. Woods filled with wolves she and her team dubbed biters, old friends and colleagues who suddenly weren’t so enthused when her name was flashed across the front pages of newspapers across Texas or the nation, or when churches and schools congratulated CRYSTLE STEWART! on their billboards, proud of their hero who would take the crown in Nha Trang. Biters: people who hated her success out of envy, the fact that she could be rich soon and leave them to obscurity forever, because that’s how things happened – it was bad enough to leave Missouri City for Houston proper, but she had left the entire South behind for downtown Manhattan, which might as well be another country.

It will all go in the book, Crystle thought, as more smocked hospital workers and photographers filtered into the OR. She’d already thought of a title: Waiting to Win. It was perfect.

Kubis had moved on. She snapped back to attention. ‘Before we were a floating hospital, the Mercy was an oil tanker. In those days, the ship was called the SS Worth. But since 1984, we’ve been entirely dedicated to military support or humanitarian efforts. And with our nine-hundred-person staff, including three hundred health experts, we can do almost everything that a standard, on-land emergency room can.’

Kubis glanced up, nodding at someone over the heads of the women. Turning on her heels, Crystle caught the eye of a younger man standing behind them, sporting the same brush cut, his hands clasped over his belt buckle. He wore pressed khakis and a dark-ribbed naval sweater, embroidered gold bars at his shoulders, no smock. He was clean-shaven and blond and obviously quite relaxed.

‘I’d like to introduce you to Lieutenant Coby Croft,’ Kubis said. ‘He’s the head OR nurse on board. He’ll be explaining how Operation Smile is making the difference for so many children in the region.’

The girls turned. Miss Canada raised her hand and wiggled her fingers.

‘If any of you’ve heard of Nurse TV,’ Kubis added warmly, now speaking to their backs, ‘you may recognize Lieutenant Croft. He did a great job of showing off the ship during their tour.’

‘You can find me on YouTube,’ Croft said, chuckling and rocking back on his heels, instigating some general tittering and exhaling among the crowd.

Crystle held up her chin, maintained eye contact and tried to look attentive. But inside – inside something trembled. The word YouTube rang like black magic, a sinister open sesame to some sealed chamber inside her. The very mention made her face tingle, her lips sting, and while Croft unclasped his hands and began rehashing a summary of medical supplies, surgical preparation, the extent of the Mercy’s health care capabilities, YouTube rumbled down into her intestines, causing a barely audible gurgle and pop. She brushed her hands against her midsection, quelling the sudden surge of discomfort.

Not here, she thought. Pay attention and forget it.

‘If I can have you all follow me,’ Croft said, passing his left hand toward a set of double doors and striding across the room. Crystle kept her eyes locked on his polished heels, letting the other girls fall into a makeshift line behind him. Taking the rear, she rubbed her exposed forearms, already feeling cold.

The video was uploaded to YouTube almost immediately after the incident. Within hours, the Video Response function was disabled; comments were so nasty, so stridently political, that deleting all racist or sexist posts would have been a tremendous undertaking. Disabling the comments, however, did nothing to halt the clip’s skyrocketing popularity. By the time Crystle was aboard the USNS Mercy, the video had surpassed its two millionth viewing.

The scene begins in long shot. The floor, the backdrop, the lights – everything is blue, overwhelmingly so, shades wavering between sapphire and denim, giving the impression that the auditorium is resting at the bottom of the sea, that viewers are being given a glimpse of some deep Atlantic twilight. Stage lights pulse in time with the beat of an extended edition of Sean Paul’s ‘Give It Up to Me’ (ft. Keyshia Cole), the serpentine, dance-hall rhythms of the track assuming the shudder and thud of chain-mine detonation, shipwrecks. The stage floor is glossy and dark, reflecting the glitter of plastic sequins hung as immense curtains, while a massive grid-like structure, divided into equal-sized compartments (reminiscent of Hollywood Squares, dominates the backdrop. A short flight of mirrored steps connects the structure and the stage floor. In each square (or cell) is the silhouette of a woman dressed in evening wear, as if posing in a display case or red-light brothel window.

The camera sweeps toward the stage, panning to the right. Closer, it’s evident that only the ground level of the anterior display case contains real women; the upper squares are stocked with evening-gowned mannequins. The focal point of the shot, though, is a solitary woman standing centre stage: an incredibly slender, olive-skinned girl with wavy, treated brown hair that reaches down between her shoulder blades. She is incredibly pretty, glowing like some phosphorescent anemone. Like the women behind her, she wears a glamorous evening gown: something slinky and black, form-fitting, blooming in a bell shape around her ankles. It’s also sparkly and reflective, much like the dark blue floor and pulsating backdrop.

As viewers get a clear view of her face, her dark eyes and white teeth and the shimmer of her earrings, a caption appears at the bottom of the screen beside the NBC peacock: U.S.A., Rachel Smith. Rachel begins to walk toward the camera, her arms loose, her hands brushing the sides of her hips. A woman’s voice, enthused and emphatic, calls out the country – U.S.A.! – triggering a swell of cheers and applause from the unseen audience.

It happens between her sixth and seventh step. It takes roughly three seconds: first, the shudder of her thighs, the slight pivot of her waist. Her upper body buckles, her right ankle tilts sharply and her heels lose their grip on the glossy floor. Then: kerplunk, Rachel goes down, hard on her ass, palms at her sides to soften the blow. But she’s up again in astonishing time, climbing on her heels with practiced dexterity, turning on cue with her right hand on her hip and smiling big for the camera. Three seconds of a forty-three-second film clip, featuring close-ups and multiple poses, a consistent smile. So practised is Rachel’s poise, so polished is her resolve to continue, that the show goes on as if there had been no error, no failure at all.

By the time Crystle was aboard the Mercy, she had watched the video ninety-four times. On one evening in early May, while Crystle was home for a visit, her mother snapped a photograph of her watching the clip. The camera caught Crystle in profile, chin resting heavily in her upturned palm. Her fingernails were manicured and white, her lips pursed, free of lipstick, puckered in a fake kiss. When Crystle found the JPEG on her parents’ computer, she immediately deleted it: the image of herself, bent over at the desk in the dark, her eyes wide and watchful – it made her sick to see it, sick to see how far things had come.

Cosmo

Cosmo